Overview

As China continues to rise to power, its ambitions rise alongside it. Today, the People’s Republic of China’s ultimate intentions are clear: it seeks to overthrow the U.S.-led order. In an effort to aggrandize itself, China hopes to dominate the Indo-Pacific region. This contest over the future of the regional and world order between the United States and China may potentially lead to massive conflict. For this reason, China poses the greatest danger to the U.S. national interest. [i]

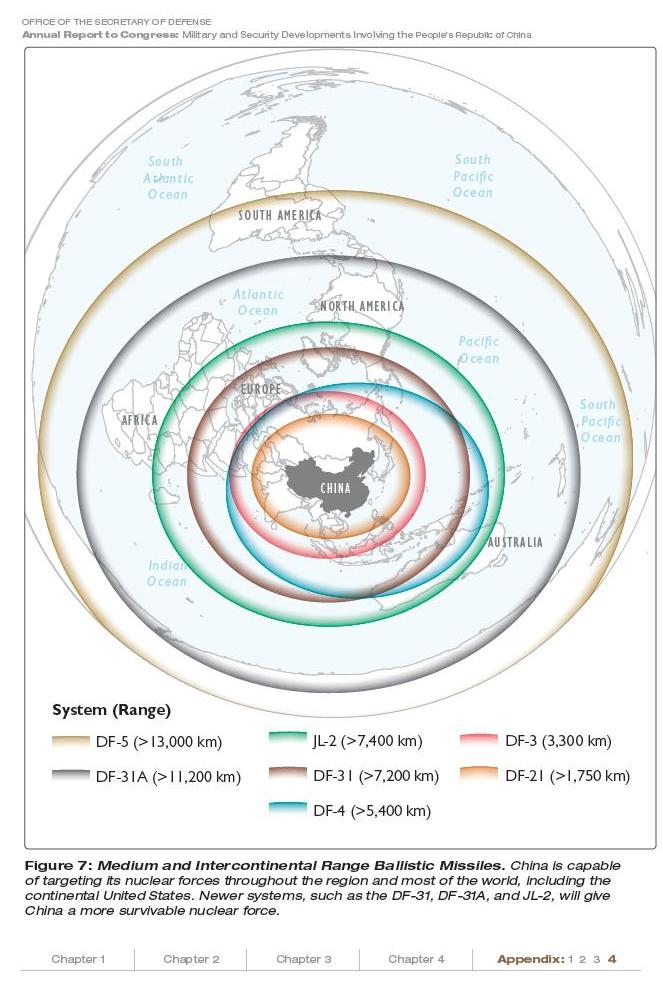

As China prepares for a potential conflict, it has developed a diverse and sophisticated arsenal of ballistic and cruise missiles. These missiles are part of a broader military modernization to enhance Beijing’s ability to assert itself in regional and territorial matters.

China’s Nuclear Program and Doctrine

China became a nuclear weapon state when it exploded its first nuclear device in 1964. Since then, China has slowly developed and modernized its nuclear weapons program using a mixture of foreign and indigenous weapons designs and technology. China’s current nuclear arsenal contains approximately 350 nuclear weapons including silo-based and road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles, short and medium-range ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Predictions about the size, status, and capabilities of China’s nuclear forces are often difficult given the secrecy surrounding China’s nuclear program and China’s extensive use of underground tunnels to store military hardware and possibly nuclear weapons. China also has refused to engage in strategic arms control dialogues that would require transparency about its nuclear forces. Generally, China views secrecy as an essential part of ensuring the survivability of its relatively small nuclear force and an integral part of its no-first-use policy. [ii]

Historically, China has maintained a nuclear doctrine based on the concept of ‘no-first-use’ (NFU), viewing its nuclear arsenal as a means of self-defense and deterrence. China’s military modernization program and upgrades to its nuclear weapons arsenal, along with its 2013 defense white paper that did not comment on China’s NFU pledge, have led some to question China’s commitment to its NFU policy. [iii] However, in its May 2015 defense white paper, Beijing reaffirmed its NFU policy stating that its nuclear weapons are for “strategic deterrence and nuclear counterattack.” [iv] In recent years China has also adopted a launch-on warning posture (LOW), called “early warning counterstrike,” which uses space and ground-based sensors and radars to detect an incoming enemy nuclear strike, allowing China to launch a strike of their own before they hit their targets.

In the last two years since 2020, China has been increasing their nuclear presence by constructing new Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) silos. They had previously maintained 20 active silos and have been constructing over 200 new silos, primarily in Northwestern China near the cities of Yumen and Hami. This expansion of capacity for active nuclear weapon capabilities is concerning because it is the first time in many years that they have done it. [viiii] This rapid action may be indicative of a new Chinese developmental nuclear policy. [x] A November 2022 Pentagon report stated that China has a stockpile of at least 400 nuclear warheads, with plans of increasing that number to 1,500 by 2035. [xi]

Ballistic Missile Program

China maintains a diverse and growing missile arsenal that it has been modernizing over the past couple of decades. China is in the process of phasing out its older missiles such as the DF-3, and DF-4, replacing them with upgraded versions including the DF-21, DF-31, and DF-31A. As it upgrades its missiles, China is incorporating ballistic missile technologies such as Multiple Independently-targeted Reentry Vehicles (MIRV) and Maneuverable Reentry Vehicles (MaRV). MIRV allows for ballistic missiles to carry multiple warheads that can be aimed at different targets within the same area, whereas MaRV is capable of maneuvering during reentry, increasing accuracy against fixed and moving targets, and even allowing warheads to avoid interception by missile defense systems. China acquired the technology and capability to develop and deploy MIRVs several decades ago, but Chinese leaders chose not to deploy missiles with this capability until recently. Over the last several years, China has developed, tested, and deployed several ballistic missiles capable of carrying MIRVs including the DF-5A and the DF-41.

China has also developed a sea-based missile arsenal. Its first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) the Type 092/ Xia-class, was launched in 1981, commissioned in 1987, and test-fired its first SLBM in 1988. The Xia Class SSBN is able to carry up to 12 JL-1 medium-range ballistic missiles that are capable of carrying nuclear warheads, giving China the third leg of its nuclear triad. It is not believed that the Xia-class submarine has ever left Chinese coastal waters due to vulnerabilities related to slow speed and a noisy engine. The Xia-class underwent a refit from 1995-2000, but it remained vulnerable to antisubmarine warfare platforms. The Xia-class was replaced by Jin-class submarines launched in the 2004-2012 timeframe.

China currently has four Type 094 Jin-class ballistic missile submarines that carry up to 12 JL-2 or JL-3 SLBMs. The Jin-class submarine is most likely China’s first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent. The U.S. DoD estimates there are 6 Jin-class submarines operational. The JL-2 SLBM is an intercontinental-range, three-stage ballistic missile that is similar to China’s DF-31 ICBM. The JL-2 has a range of more than 7,200 km and is equipped with either a single MT nuclear warhead or three to eight smaller MIRV’d warheads. The JL-3 is a newer SLBM, introduced sometime around 2021, with a longer range of more than 10,000km and can contain multiple warheads.

According to the Department of Defense’s Annual Report to Congress on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022, China’s ballistic missile arsenal contains around 600+ SRBMs, 500+ MRBMs, 250+ IRBMs, and 300 ICBMs. [v]

In June 2022, a DOD report on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) indicated that China possesses 400 DF-26 intermediate-Range Ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The DOD estimates that the DF-26 has a range of 2,500 miles, rendering it capable of striking Guam, giving it the nickname “Guam Killer” by Chinese media. [vi]

On August 4th, 2022, China began a three day exercise in which they launched 11 ballistic missiles. The exercises come as Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, visited Taiwan against the multiple threats from Chinese leadership.

Cruise Missiles

China has been actively developing cruise missiles with foreign assistance, primarily from Russia. It already possesses nearly a dozen varieties of anti-ship missiles, such as the Russian-made SS-N-22, and is pursuing land-attack cruise missiles. According to the Department of Defense, China now has the capability to domestically produce highly accurate land-attack and anti-ship cruise missiles. The CJ-10 (DH-10) and CJ-100 (DF-100) ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs) have ranges of 1,500 and 2,000km, respectively. As of 2022, the U.S. DoD estimates China has more than 300 GLCMs. Their YJ-21 hypersonic cruise missile has a range of 1,000-1,500km and flies at a speed of up to 10 Mach.

In November of 2022, China revealed an air-launched version of their YJ-21 with the designation 2PZD-21. Like the YJ-21, the 2PZD-21 is a highly maneuverable hypersonic missile that can be fired from their H-6K bomber.

Hypersonic Weapons

In recent years China, Russia, and the United States have renewed efforts to develop hypersonic weapons as part of their conventional and nuclear arsenals. Hypersonic weapons are ultra-high-speed weapons that fly along the edge of space and accelerate between Mach 5 and Mach 10. Given their rate of speed and nonballistic trajectory, hypersonic weapons are difficult for current ballistic missile defense systems to intercept. Additionally, their low flight altitude prevents detection by terrestrial-based radars, as they are blocked by the curvature of the earth.

Since 2014, China has carried out several tests of its hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV). The HGV, the DF-ZF, is launched during the last stage of a missile and can reach nearly 7,500 mph (Mach 10), as well as a maneuver to avoid missile defenses and zero in on targets. This weapon can be configured to carry a nuclear or conventional warhead and China claims it is precise enough to attack ships at sea. Hypersonic weapons could also compress the number of times leaders have to make decisions in times of crisis because they can strike much faster than other weapons.

In 2018, China started trials for their Starry Sky-2 (Xingkong-2) Waverider HGV cruise missile. The glider uses the shock waves produced by hypersonic flight to help propel it forward and keep it in the air.

Currently, the DF-ZF is carried by the DF-17 HGV-armed MRBM, which was first fielded in 2020. China continues to develop its hypersonic weapon technology, with the testing of an ICBM-range HGV that traveled 40,000km in July 2021, flying around the world and barely missing a target back in China.

According to a leaked classified daily briefing by the J-2 dated February 28, 2023, the DF-27, an HGV-equipped IRBM, was successfully tested three days earlier on Feburary 25, flying for 12 minutes and traveling 2,100km. J-2 believes that land attack and antiship variants have already been deployed.

Close-Range Ballistic Missiles (CRBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (Km) |

| M-7/8610 | Solid/Liquid | Single HE/Chemical | Road-Mobile | 150 |

| DF-12 | Solid | Single | Road-Mobile | 280 |

Short Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (Km) |

| DF-16 | Solid | MIRV (3) Conventional/Nuclear | Road-Mobile | 700+ |

| DF-15 | Solid | Single HE/Nuclear/Chemical | Road-Mobile | 725-850 |

| DF-11 | Solid | Single HE/Nuclear/Chemical | Road-Mobile | 300-600 |

Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| DF-21D | Solid | Maneuverable Conventional/Nuclear | Silo/Road-Mobile | 1,500+ |

| DF-21/21A/21B/21C | Solid | Single HE/Nuclear | Road-Mobile | 1,750+ |

Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| DF-3 | Liquid | Single HE/Nuclear | Transportable | 3,000 |

| DF-26 | Solid | Conventional/Nuclear | Road-Mobile | 3,000 |

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| DF-4 | Liquid | Single Nuclear | Transportable | 5,500+ |

| DF-5A/5B | Liquid | Single Nuclear/5 MIRV | Silo | 13,000+ |

| DF-31 | Solid | Single Nuclear/3-5 MIRV | Road-Mobile | 7,200 |

| DF-41 | Solid | Single Nuclear/up to 10 MIRV | Silo/Road-Mobile | 12,000 |

Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs)

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Submarine Class | Range (km) |

| JL-1 | Solid | Single | Xia | 1,700+ |

| JL-2 | Solid | Single/3-4 MIRV | Jin | 7,200 |

| JL-3 | Solid | Single/MIRV | Jin/Type 094 | 10,000 |

Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs)

| Model | Launch Mode | Warhead Type | Range (km) |

| YJ-63 | Air | Conventional | 200 |

| CJ-10 | Ground | Conventional or Nuclear | 1,500+ |

| CJ-20 | Air | Conventional/Nuclear | 2,000+ (est.) |

Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs)

| Model | Launch Mode | Warhead Type | Range (km) |

| YJ-12A | Air/CM-302 variant can be launched from air, sea, and land platforms | Single HE | 460 |

| YJ-18 | Surface ship/Submarine | Single HE | ~540 |

| YJ-83/83J | Frigates, corvettes, modernized ships, H-6 bombers. | Single HE | 180 |

| YJ-62 | Mounted on newer surface combatants such as LUYANG II class DDGs | Single HE | 400 |

Hypersonics

| Model | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| DF-ZF Hypersonic Glide Vehicle (HGV) | Liquid (scramjet propulsion engine) | Conventional or Nuclear (depends on the missile the HGV is used with) | Can be equipped with a variety of missiles | Varied (depends on the missile the HGV is used with) |

| DF-17 (MRBM) | Solid | Conventional or Nuclear | Road-Mobile | 1,800 – 2,500 |

| DF-27 (IRBM) | Solid | Conventional or Nuclear | Road-Mobile | 5000-8000km |

Map of China’s Missile Ranges

Click Here to Read MDAA’s Report on China’s Ballistic Missile Capabilities

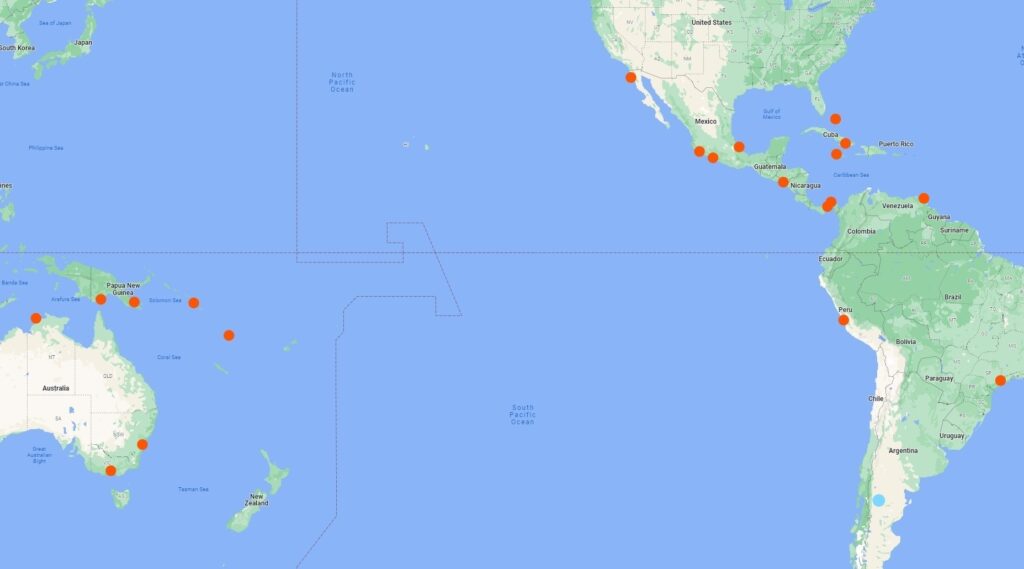

China’s Expansion

Red Circles: Ports owned or controlled by China

- Australia – Darwin, Melbourne, Newcastle (Obtained October 2015, September 2016, June 2018)

- Brazil – Paranaguá (Obtained February 2018)

- Cuba – (Obtained December 2021)

- El Salvidor – (Obtained 2019)

- Jamaica – (Obtained April 2015)

- Mexico – Manxanillo, Lazaro Cardenas, Veracruz

- Panama – Balboa, Colon (Obtained March 1997, May 2016)

- Papua New Guinea – Daru (Obtained September 2018, December 2020)

- Peru – Lima and Chancay (Obtained April 2019)

- Solomon Islands – (Obtained October 2019)

- St. Johns – Harbor reconstruction (2021)

- Trinidad – (Obtained June 2013)

- Vanuatu – Luganville (Obtained April 2018)

Blue Circle: Space Station with 16 story antennae

Many of the ports shown can be used to port military vehicles to refuel and make repairs. Notably, pictures show that the port in Peru is constructed to be able to house extremely large ships, as well as submarines. Their JL-2 ballistic missile launched from submarines would be able to hit any part of the United States from this port, and their new JL-3 has a range great enough to hit the continental US from outside the Pacific Ocean, giving it full range from their port in Brazil. Both of these ports are inside the Guam defense, and on the other side of the US from the GBI defenses.

Recent News

- Analysts have used satellite imaging to argue that China is practicing missile strikes on Taiwan and Guam. [vii] A Chinese-controlled Taiwan would be disastrous to the United States’ interests in Asia. Taiwan—being China’s most direct link to the first island chain—would offer the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) the opportunity to project its power in the region further. Moreover, China’s conquest of Taiwan could cause many American allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific to bandwagon with China. As a U.S. territory in the region, Guam is vital for the United States’ ability to project power in the Indo-Pacific. Because China’s growing missile threat directly endangers both of these islands, the U.S. must focus on strengthening its missile defense capabilities. [viii] Experts have advised significantly increasing defense capabilities, like the THAAD missile defense system for targeting ballistic missiles, and an Aerostat sensor system like the JLENS for missile detection throughout the surrounding second island chain. While the US does have one THAAD battery located in Guam, more cost-effective low altitude defense systems are needed. China has made great strides in September with their DF-17 and DF-ZF hypersonic missile technology, which increases demand for more advanced Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI) missile defense systems around Guam. The Pentagon is currently exploring these the integration of GPI upgrades into current THAAD and Aegis systems.

- Russia says it held talks with China on missile defense

- ‘A new arms race’: Satellite images, maps and records reveal huge surge in China’s missile production sites

- China Building SAM Sites That Allow Missiles To Be Fired From Within Bunkers

- Taiwan seeks faster NASAMS from U.S. to plug critical air defense shortfalls.

References

[i] https://www.belfercenter.org/thucydides-trap/overview-thucydides-trap

[ii] https://armscontrolcenter.org/countries/china/

[iv] http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm

[v] https://www.defense.gov/CMPR/

[vi] https://taskandpurpose.com/analysis/military-guam-china-war-taiwan/

[viii] https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2022/05/guam-needs-better-missile-defensesurgently/367275/

[viiii] What’s Driving China’s Nuclear Buildup? – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

[x] China’s Nuclear Doctrine: Debates and Evolution – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

[xi] 2022 Pentagon Report on Chinese Military Development – USNI News