Overview

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) has relied heavily on missile capabilities in order to secure the regime against foreign threats, on the one hand, and to advance its regional revisionist policies, on the other. The reliance of the Islamic Republic on missile capabilities is originated in two events. First, after the Revolution, the new regime’s purging of top military commanders of the monarchy including the Imperial Iranian Air Force (IIAF) commanders deprived Iran of the cadre who could operate the Iranian aircraft skilfully. This, in addition to ending of the military contracts with the West particularly the United States as the former Iranian partners or allies left the country wanting in air force capabilities. Second, the advent of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 necessitated an alternative to the air force, which was now fragile, to reciprocate the Iraqis’ aerial war efforts.

The Islamic Republic’s first use of missiles dates back to March 1985, during the Iran-Iraq war, after it purchased Scud missiles from Libya and North Korea. Since the end of the war, however, IRI has used missiles in different theatres and against various groups and states. The table below features the operational use of ballistic missiles by the the Islamic Republic since the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988 with the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK), an Iranian dissident Organization, being the first target.

Use of Ballistic Missiles in military operations since the Iran-Iraq War

| Date | Codename | Target | Apparent Rationale | Missiles Used |

| November 1994 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Retaliation for MEK attacks | Three Shahabs (likely shahab-1s or Shahab-2s) |

| November 1994 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Retaliation for MEK attacks | Three Scuds (likely Shahab- 1s or Shahab-2s) |

| June 1999 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Unclear; likely retaliation for MEK assassination | Scud- B (assumed) |

| November 1999 | N/A | MEK base in Iraq | Unclear; likely retaliation for MEK assassination | Scuds (assumed) |

| April 2001 | N/A | MEK bases in Iraq (at least 3 different locations) | Unclear | 44 to 77 Scuds (likely Shahab- 1s or Shahab- 2s) |

| June 2017 | Operation Laylat al-Qadr | ISIS targets in Deir ez-Zour, eastern Syria | Retaliation for ISIS terror attack on Iranian parliament and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s shrine | Six SRBMs (Zulfiqars and Qiam-1s) |

| September 2018 | N/A | Kurdish opposition parties in Iraqi Kurdistan | Uptick in tensions between Tehran and Kurdish insurgent groups | Seven SRBMs (Fateh- 110Bs) and drones |

| October 2018 | Operation Zarbat al-Moharrram | ISIS targets in eastern Syrian city of Hajin | Retaliation for ISIS terror attack in Ahvaz | Six SRBMs (Zulfiqar and modified Qiams) |

| January 2020 | Operation Shahid Soleimani | Bases in Ain al-Asad and Erbil housing US forces | Retaliation for US killing of IRGC-QF Chief Qassem Soleimani and Iraqi militia leader Abu-Mahdi al-Muhandis | 16 SRBMs (Fath-313 and modified Qiams) |

| March 2022 | N/A | Alleged Israeli presence in Iraq; home of a Kurdish oil tycoon | Retaliation for alleged Israeli attack from Iraqi soil | 10 SRBMs (Fath-110) |

| September 2022 | N/A (assumed Rabi’a 1) | Iraqi Kurdistan; targets affiliated with Kurdish-Iranian opposition groups | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests inside Iran | 73 SSMs reported.Assumed solid-propellant due to size and plume color. Later revealed as Fath- 360 CRBM. |

| November 2022 | operation Rabi’a 2 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests inside Iran | Apparently 12 canisters on TELs. Assumed at least 1 Fath-360 CRBM. |

| November 2022 | Operation Rabi’a 2 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Allegedly responding to Kurdish support for protests inside Iran | No clear number of projectiles fired. Assumed at least 1 Fath-360 CRBM. |

Source: Foundation for Defense of Democracies, “Arsenal: Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program” 2023

Iran and its Proxy Groups

In order to undermine the United States and its allies in the Middle East, Iran has developed a regional military and political network termed as the “Axis of Resistance”. The network includes Iran, Syria, Hezbollah, Iraqi Shia militia, the Yemeni Huthis, and some Palestinian militants. Iran has provided the militia within such network with munitions, the most important of which have been rockets and missiles. Thus far, the US regional partners at which projectiles have been fired include Israel, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates.

| Proxy/Partner Name | Missile Transferred | Targets |

| Hezbollah (Lebanon) | Fateh-110, PGM kits, subterranean missile factories | Assumedly Israel |

| Huthis (Yemen) | Modified Scud variant: Burkan-1106 and Houthis (a.k.a. Ansar Allah); Yemen modified Qiam-1 variants: Burkan-2H,107 Burkan-3/Zolfaghar.108 More recently, the Hatem (assumed Kheybar Shekan), Karrar (assumed Fateh-110 or Fateh variant), and Falaq (assumed Qiam-2) | Saudi Arabia, UAE, Israel in the future potentially |

| Shi’ite Militias (Iraq) | Fateh-110, Zulfiqar. No known transfer to militia groups in Syria directly from Iran. | Assumedly Israel or U.S. and coalition forces in Iraq |

| Asad Regime (Syria) | Fateh-110, missile factories | Syrian rebels, potentially Israel |

Source: Foundation for Defense of Democracies, “Arsenal: Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program” 2023

Iran’s Current Missile Technologies

Iran’s ballistic missiles could be used as a political weapon against rival states and the continues to flaunt its arsenal with acts of intimidation like the 10-day war drills executed at the end of June 2011.

The utility of the Islamic Republic’s missiles is limited due to poor accuracy and TEL availability and delays. War games coordinated have promoted the ‘made in Iran’ label, but also revealed an unexpected look at underground silos. These tests showcasing Iran’s missile forces are likely meant as a show of force to the West. More recently, on January 22nd, 2018, Iran continued its annual series of large-scale war exercises in the Strait of Hormuz. Codenamed Mohammad Rasoulallah, during the series Iran both tested its infantry and fired several precision missiles at targets in the Sea of Oman in order to demonstrate its ballistic missile power.

Iran’s message has been one of growing self-sufficiency despite the establishment of the Iranian nuclear deal. Although the extent of Iran’s military arsenal is unknown, many defense analysts note that Iranian engineers have had decades to copy and modify designs obtained from abroad, receiving missile technology from countries such as North Korea, Russia, and China.

Investments to develop a local liquid-propellant missile industry began with Iran’s missile purchases in the 1980s. They began production on their own version of the Scud-B missile, the Shahab-2, in 1994. The Islamic Republic began receiving the No Dong missile from North Korea in the mid-1990s and began developing their own version of the missile, the Shahab-3. The first successful test of this new missile was in 1998. The Iranians have conducted multiple successful tests of the Shahab-3, and in 2004 began work on modifying the Shahab-3 to be more accurate, and harder to track in flight. The Iranian objective to develop the Shahab-3 without assistance resulted in the production of the longer-range Ghadr-1. In recent years, Iran has also developed a finless version of the Shahab-3, known as the Zulfiqar missile. Used in June of 2017 against the Islamic State, the short-range ballistic missile is thought to have a range of about 700km. Iran’s ability to produce and improve its technologies has been steadily increasing over the years.

Iran has also been making steps forward in its space program. Using multi-stage variants of the Shahab-3, known as the Kavoshgar and Safir rockets, Iran has used both to send satellites into low orbit, and recently claimed to have successfully sent living organisms into space. Since 2008, Iran has conducted multiple successful tests of the Safir launch vehicle and has also revealed the larger two-stage Simorgh space-launch vehicle. Iran’s space-launch program provides the country with information critical to its ballistic missile capability. Indeed, the information provided by the employment of space-launch vehicles can directly translate to intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Iran has also developed a solid-propellant version of the Shahab-3, known as the Sejjil (Ashura) missile system. This is a more accurate version of the Shahab-3 and has a longer range as well. The solid-fueled system makes the Sejjil a more reliable attack option for Iran, and therefore makes them a more formidable player in the region.

Iran, despite limitations on their missile testing laid down in the Iranian nuclear deal, has continued to test ballistic missile technology. The deal prohibits Iran from testing any missile designed to carry a nuclear warhead for a period of eight years, but not from testing other missiles. Iran has pushed this framework on multiple occasions, most recently on June 18th, 2017, when Iran tested the Khorramshahr missile. The specifications of the missile are unknown, and therefore it is as yet unclear if the test violated this agreement.

Iran’s missile strikes against targets in Syria and Iraq (June 18, 2017, and September 08, 2018, respectively) suggest a pattern to Iran’s missile attacks. In both strikes, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was sent over the target area to conduct a battle damage assessment, one liquid-fueled ballistic missile and around six solid-propellant ballistic missiles. Current conflicts in the Middle East have served as proving grounds for new missiles and practice for Iranian missile forces.

As far as nuclear facilities, Iran’s abilities were limited by the JCPOA nuclear deal. Currently, Iran only has one facility, Natanz, in which they are permitted to conduct uranium enrichment. The Iranian facility at Arak continues to produce Heavy Water, but is no longer permitted to enrich Plutonium, and is under monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency. In January of 2016, Iran announced they had removed the core of the Arak reactor, and filled it with concrete, an important stipulation of the deal.

Most recently, Iran unveiled a new missile, the Khaibar Shekan, that has been reported to have a range of 1,450 kilometers or 900 miles. The Khaiibar Shekan uses a solid fuel propellant and is claimed to have been produced domestically.

Iran’s Missile Production and Deployment

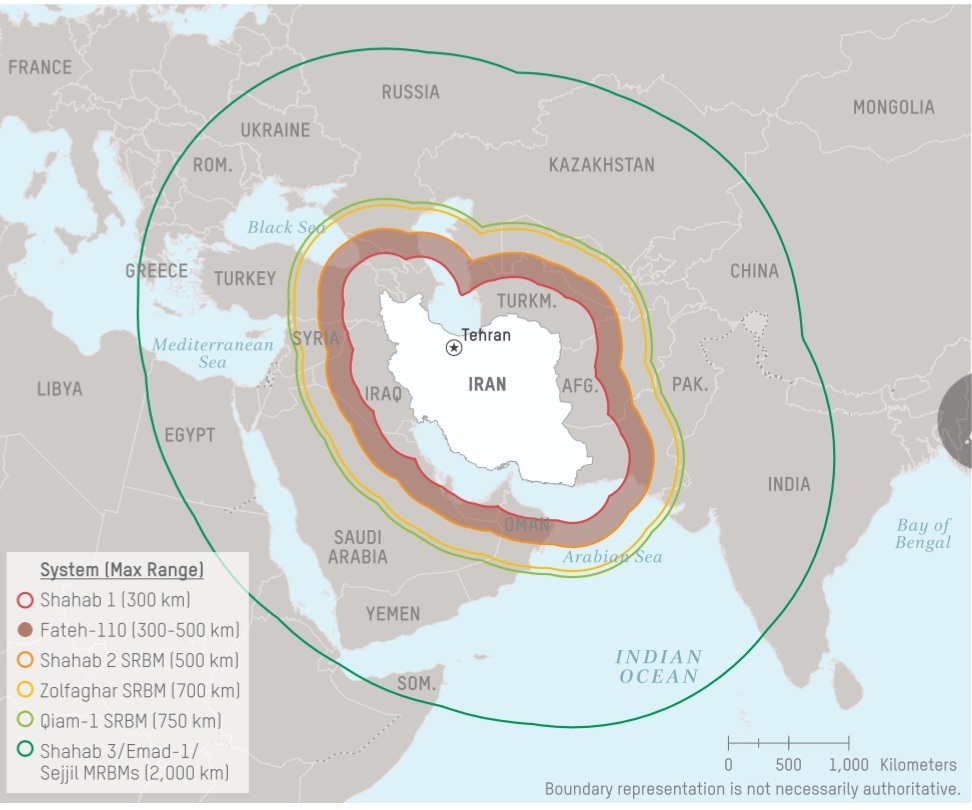

The distance from Tehran to our military bases in Baghdad, Iraq is around 712 kilometers or 442 miles; to Kuwait City is 784 kilometers or 487 miles; to Manama, Bahrain is 1062 kilometers or 660 miles; to Kandahar, Afghanistan (near Helmand) 1394 kilometers or 866 miles; to Doha, Qatar, the distance is around 1164 kilometers or 723 miles.

According to the INF Treaty, a short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) is defined as one with a “range capability equal to or in excess of 500 kilometers but not in excess of 1000 kilometers”, while the Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) ranges from 1000 kilometers up to 5500 kilometers. Iran has stated that it already possesses missiles with ranges up to 1,240 miles or 2,000 kilometers.

Though the distances listed on our website represent theoretical air distances and flight trajectories may vary, further advancement of Iranian weapons capabilities places our allies as well as our bases in the Gulf in great danger.

Future Outlook

Iran’s ability to produce new liquid-propellant missiles is constrained by their ability to develop new liquid-propellant engines. Seeing that Iran’s primary supplier of such engines is Russia and Ukraine, who follow Missile Technology Control guidelines, Iran must rely on themselves. Building a missile with a longer range requires a larger missile; therefore, the most logical configuration for Iran to produce a long-range weapon is to produce a liquid propellant missile or a space-launch vehicle with enhanced performance.

More concerning is Iran’s growing solid-fuel capabilities. In 2008, Iran test-launched the new Sejjil ballistic missile, which is a solid-fueled medium-range ballistic missile that has a payload-range capacity that represents a marked improvement over the country’s liquid-propelled Shahab-3. In addition to improved range and capacity, the Sejjil has improved battlefield capabilities as well, requiring less time to be erected and launched than a liquid-fueled missile. Testing and production of the Sejjil also have significant strategic implications, underlining Iran’s shift away from liquid-fueled missile engines–that are heavily reliant on foreign technology–and towards domestically designed and produced solid-fuel rocket motors. As of February 2022, Iran has continued its shift to solid-fuel propellants with the intro8duction of the Khaibar Shekan. Iran’s improving ability to produce solid-fueled missiles domestically highlights the country’s determination and ability to advance its missile capabilities while becoming more self-sufficient. Iran has now tested the Sejjil-2, a more stable rocket, with improved accuracy in comparison to the Sejjil-1, and Shahab model rockets.

It is likely that Iran will develop an intercontinental-range ballistic missile using technology produced indigenously, either from the country’s ballistic missile or space launch program, instead of solely relying on outside technical assistance from countries such as North Korea. Iran is approximately a decade away from obtaining an ICBM capable of reaching the U.S. homeland. Under the framework of the JCPOA deal, Iran was banned from developing or testing any rockets capable of carrying a nuclear warhead for eight years. After the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, however, Iran has stated it will resume its missile development if Europe is unable to guarantee stable Iranian oil sales. The lack of plutonium enrichment allowed under the Iran deal also limits the progress Iran can make in developing a weapon cable to deliver a nuclear payload to the United States; however, this is limited by the effectiveness of the monitoring done by the UN. Despite the JCPOA deal, U.S. forces and allies in the Middle East still remain under threat from Iranian ballistic missiles.

In an attempt to continue growing Iran’s space program, Iran tested the Zuljanah satellite carrier on June 26, 2022, to publically demonstrate its ability to deploy satellites.

Iran’s Ballistic Missile Arsenal

Close-Range Ballistic Missiles (CRBM)

| Model | Meaning | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| Fadjr-5 | Dawn-5 | Solid | High Explosive/Chemical | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 75 |

| CSS-8 (M-7) | Solid/Liquid | Conventional/Nuclear-Capable | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 150 |

Short Range Ballistic Missiles (SRBM)

| Model | Meaning | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| Fateh-110 | Conqueror-110 | Solid | Conventional/WMD Capable | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 200-300 |

| Fateh-313 | Conqueror-313 | Solid | Conventional | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 500 |

| Shahab-1 (Scud-B) | Meteor-1 | Liquid | High Explosive/WMD Capable | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 300 |

| Shahab-2 (Scud-C) | Meteor-2 | Liquid | High Explosive/WMD Capable | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 500 |

| Zulfighar (aka Korramshahr) | Lord of the Spines (Khorramshahr is a city in Iran) | Solid | Cluster | Deployed | 700 |

| Qiam | Uprising | Liquid | Conventional | Deployed/Road-Mobile | 700-800 |

| Raad-500 (aka Zouhair) | Thunder-500 (Zouhair: Name of the companion of Imam Hussein at Karbala) | Solid | Unknown | Deployed | 500 |

Medium Range Ballistic Missiles (MRBM)

The Testing of Kheibar (Khoramshahr 4) (Photo: Tasnim News Agency)

| Model | Meaning | Propellant | Warhead Type | Deployment | Range (km) |

| Shahab-3 | Meteor-3 | Liquid | High Explosive/Nuclear capable | Deployed/Silo & Road Mobile | 1,000-1,300 |

| Sejjil (aka Ashura) | Baked Clay (Ashura: The commemoration day of the Third Shi’ite Imam) | Solid | Conventional | Deployed/Road Mobile | 2,000 |

| Emad | Pillar | Unknown | Conventional/Nuclear capable | Testing/Road Mobile | 1,700 |

| Khaibar Shekan | Breaker of Kheibar | Solid | Unknown | Testing/Road Mobile | 1,450 |

| Kheibar (Khoramshahr 4) | Name of a battle led by Muhammad against Jewish tribes | Liquid | Conventional/Nuclear capable | unknown | 2,000 |

| Qadr-474 | Name of a holy Islamic holiday | Unknown | Conventional/Nuclear capable | deployed/vessels | 2,000 |

| Haj Qasem | Name of the IRGC’ Quds Force Commander who was killed by the United States in 2020 | Solid | Conventional/Nuclear capable | deployed/Road Mobile | 1,400 |

| Abu Mahdi | Name of the Commander of the Popular Mobilisation Forces, an Iranian proxy group, in Iraq who was killed by the United States in 2020 | Solid | Uknown | deployed/Road-Mobile | 750 |

| Hoveizeh/Hoveyzeh | A city in Khuzestan province in Iran | Solid | Conventional | deployed/Road Mobile | 1,350 |

| Paveh | A city in Kermamshah province in Iran | Solid | Unknown | deployed/unknown | 1,650 |

Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs)

| Model | Meaning | Warhead Type | Cruise Missile Type | Range (km) | Launch platform/Targets | Country of Origin | Status |

| Soumar | Named after a town in Iran | Conventional | Long-range land-attack cruise missile | 2,500 | Surface/Surface | Iran | unknown |

| Meshkat | Light Source | Conventional | Long-range land-attack cruise missile | 2, 000 | Land, Sea, Air/Surface | Iran | In Development |

Hypersonic Missiles

In the latest development, on June 6, 2023, Iran announced that it succeeded in building an idigenous hypersonic missile. In his interview with the BBC Persian Television, Tal Inbar, the MDAA senior fellow, confirmed that the Iran’s new missile capability is a genuine development. However, Mr. Inbar, continued to assert that Israel is capable of defending itself against Iran’s hypersonic missile threat by drawing upon Israel’s layered missile defense system. [i]

Specifications

| Model | Meaning | Speed | Propellant | Range |

| Fattah | Conqueror | 16,000-18,500 km/hour (13-15 Mach) | Solid | 1400 km |

Main Characteristics

- Two stags, unique configuration

- Steering:

- 1st stage – Foreword aerodynamic fins.

- 2nd – combined sustainer TVC and RV aerodynamic fins (the same as for the booster).

- Assessed dimension:

- Body diameter – about 1 meter.

- Length – about 15.3 m.

- Weights: Take off weight – Circa 12 tons, almost 9-ton propellants. • RV – 1 ton; Warhead 350 to 450 Kg.

- Guidance and navigation: INU and GNSS (GPS & GLONASS).

- Assessed CEP accuracy – 10 to 25 m

- Warhead – HE

“Fattah” missile re-entry vehicle (RV)

- RV with 4 segments:

- 1- Rear segment with 4 aerodynamic thick fins and rocket motor (sustainer) with flex nozzle.

- 2 – Warhead section

- 3 – Front section

- 4 – Nose tip

Trajectory profile – phases of the missile’s flight (based on the official Iranian released video)

- First phase: boost by rocket motor, burnout, and separation of the RV from the first stage.

- Second stage: Ballistic flight (depressed), later – ignition of the sustainer located in the rear of the RV while out of the atmosphere. Then, performing 3 dimensional maneuvers, reentry into the atmosphere in a pull-up maneuver with the same 4 fins.

- Third phase: Pitch down

maneuver towards target, with the 4 fins and (depends on range) the sustainer still burning up to the target in a preprogramed approach angle.

Click here to read more

Iranian Ballistic Missile Ranges

Source: Defense Intelligence Agency estimates of missile ranges, 2019

Iran’s Satellite Launched Vehicles (SLV) program

Iran recognizes the strategic value of space and counterspace capabilities. Nevertheless, its attempts to advance its space program has not rendered much success. Iran’s simple SLVs are only able to launch microsatellites into low Earth orbit and have proven unreliable with few successful satellite launches. The Iran Space Agency and Iran Space Research Center—which are subordinate to the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology—along with Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics, oversee the country’s SLV and satellite development programs.

Selection of Satellite Launched Vehicles (SLV) Tested By Iran

| Name | Meaning | First Revealed/Tested | Last Tested | Motor/Engine | Stages | Length (m) |

| Safir | Ambassador | 2008 | August 2019 | Liquid | 2 | 22 |

| Simorgh | Phoenix | 2010/2016 | December 2021 | Liquid | 2 | 27 |

| Qased | Messenger | 2020 | March 2022 | Hybrid (currently: liquid-solid-solid) | 3 | 17.75-18.1 |

| Zuljanah | Name of the first Shi’ite Imam’s horse | Assumeed late 2020/early 2021 | June 2022 | Hybrid (currently: solid-solid-liquid) | 3 | 25.5 |

| Qa’em-100 | Upright-100 | November 2022 | November 2022 | Solid | 3 | 20 |

Source: Foundation for Defense of Democracies, “Arsenal: Assessing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Ballistic Missile Program” 2023

Iran’s Nuclear Program Overview

Facilities of Key Concern

| Facility | Type | Purpose | Status |

| Natanz | Uranium Enrichment Plant | Fissile Material Production | Currently producing up to 5% low-enriched uranium

Production of up to 20% enriched uranium is suspended per the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) Natanz is the only facility that can be used to enrich uranium to peaceful levels (3.67%) |

| Fordow | Uranium Enrichment Plant | Fissile Material Production | JCPOA suspended all enrichment and nuclear R&D at the facility |

| Parchin | Military Research Facility | Suspected high-explosives research center

Possible nuclear weapons research activities |

Satellite imagery indicates increased construction at the site

IAEA cites “credible” intelligence that Iran has engaged in nuclear weapons research at Parchin. The site may have been cleansed to conceal activities from the IAEA |

| IR 40 (Arak) | Heavy Water Nuclear Reactor | Research Reactor

A potential source of plutonium for the manufacture of nuclear weapons |

Decommissioned as a possible producer of Plutonium as part of the JCPOA.

In January 2016, the core of the reactor was removed and filled with concrete. Additionally, members of the P5+1 have agreed to assist Iran in redesigning the facility to produce and research isotopes for medical purposes. |

Iranian UAV Threat

The Iranian military’s Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) arsenal consists of multiple types of UAVs; possibly more than 20. Most of the UAVs used by the Iranian military are poorly made, but it does have some more advanced types.

The most capable and advanced UAVs in the Iranian arsenal are based on the designs of U.S. and Israeli UAVs that were shot down in Iran. Advanced UAVs that Iran is known to have shot down and recovered include the U.S. MQ-1 “Predator”, which was displayed by Iran on October 01, 2016. Iran’s Shahed-109 is a close copy of Israel’s Hermes 450. The Shahed-109 specifically has been operated in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq and has a 24-hour endurance capability.

Selection of Iran’s UAV Inventory

Selection-of-Irans-UAV-Inventory_4Iran’s Worldwide UAV Exports

The Islamic Republic’s actual engagement in exporting unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) beyond the Middle East dates back to 2008 around which time the Iranians sold some drones to the Sudanese. (Prior to that, the Islamic government had already discussed equipping Venezuela with drone technology.) Since 2008 Iran has expanded its global footprint. Therefor, as the New York Times has noted, “Tehran has quietly stepped up the sale of drone technology to countries outside the Middle East as it seeks to become a player in the international market.”

The expansion of Iran’s areas of export, however, may have its own dire consequences for those regions that these flying machines are sent to. For instance, currently, Iran has the potential to export its drones to the Balkans. However, as the Jamestown Foundation warns: “Tehran’s entry to the Balkan region’s drone industry opens the door to IRGC involvement across NATO’s southeastern flank.”

The table below discloses the countries to which the Iranians export their drones.

| Country | Starting Date of Export | Designation | Targets |

| Algeria | 2023 | N/A | Morocco |

| Ethiopia | 2021 | Mohajer 6 | Tigrayan Rebels |

| Russia | 2022 | Shahed 136, Mohajer 6 | Ukraine |

| Sudan | 2008 | Ababil 3 | Rebel Groups |

| Tajikistan | 2022 | Ababil 2 (factories) | Presumably Ukraine |

| Venezuela | 2012 | Mohajer 2, Mohajer 6 | N/A |

Photograph: Times of Israel

Iranian Missile Defense Overview

Although Iran’s missile defense architecture is currently reliant on imported Russian technology, its deployment near key Iranian nuclear facilities poses an operational challenge to the United States and its allies, primarily with regard to potential military options in the case of an Iranian nuclear breakout.

| DESIGNATION | BASING | STATUS | TARGETS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bavar-373 | Land | Development | Cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and aircraft |

| S-300V | Land | Deployed | Aircraft (SA-12A Gladiator interceptor); tactical ballistic missiles and cruise missiles (SA-12B Giant interceptor) |

Bavar-373 The Bavar-373 is Iran’s version of Russia’s S-300 surface-to-air defense system. It is said that the Bavar-373 encompasses technology that is “more advanced” than the S-300. Iran’s system is intended to intercept cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, as well as other airborne targets. Iran unveiled the domestically-produced Bavar-373 system in 2016.

S-300V In 2016, Russia delivered S-300 air defense systems to Iran that have been deployed at Iran’s Fordow nuclear site, which is an underground facility formerly used to enrich uranium. Although the facility has been inactive since the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015, Iranian military officials claim the systems will be fielded to “protect Iran’s nuclear facilities under any circumstances.”

Countering the Iranian Threat

The Iranian ballistic missile threat puts at risk U.S. forces, partners, and allies in the Middle East and Europe. In response, the United States, along with key U.S. partners and allies in Europe and the Middle East, has undertaken a variety of measures to mitigate the risk posed by Iran’s improving ballistic missile arsenal.

Regional U.S. Countermeasures

To protect U.S. forces, allies, and partners in the Middle East, the United States began deploying missile defense systems throughout the region in the 1990s and 2000s to counter the threat posed by the proliferation of ballistic missiles in nations like Iran. Over time, advanced hit-to-kill systems such as Patriot/PAC-3 and the SM-3 equipped with Aegis BMD-capable vessels were deployed in the region.

Missile Defense and the Gulf Cooperation Council

Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, also began purchasing Patriot/PAC-2 air and short-range missile defense systems from the United States. As Iran’s ballistic missile and nuclear programs improved, so to did the missile defense capabilities of the Gulf States. Today, the United States is leading substantial efforts to increase missile defense cooperation within the Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) to create a region-wide BMD architecture that, in conjunction with U.S. systems, is capable of regional defense and early warning.

U.S. Missile Defense Cooperation with Israel

The U.S. Congress has also continued to authorize financial and technical support for Israel’s ballistic missile defense program, which is designed to counter ballistic missiles and projectiles from Iran, as well as Iranian-backed groups such as Hezbollah. Historically, the relationship between Israel and Iran has been one of antagonism, and the rhetoric of Iranian leaders has reflected this. Regional tension between the two nations culminated in 2005 when former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad stated that he wanted to wipe Israel “off the map.” Bilateral missile defense cooperation between Israel and the United States is a staple of regional stability and security in the Middle East and will likely remain strong for the foreseeable future.

The European Phased Adaptive Approach

Iran’s growing long-range missile and nuclear programs have triggered security responses from the U.S. in Europe, which initially pushed for the deployment of U.S. silo-based missile interceptors in Poland and tracking radar in the Czech Republic to defend against potential Iranian ballistic missiles. This initial U.S. strategy has been altered by the Obama Administration, which created the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) that–over the next ten years–aspires on installing regional missile defense in Europe through the deployment of Aegis sea-based BMD and Aegis Ashore. This new approach uses spiral development that includes existing capabilities such as SM-3 and rapid-ground base missile development to defend Europe against Iran’s improving long-range ballistic missile capabilities.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

In July 2015, the E3/EU+3 (China, France, Germany, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy) and Iran agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which is designed to ensure Iran’s nuclear program remains exclusively peaceful. Implementation of the JCPOA marked a diplomatic high point between the United States and Iran and has succeeded in curtailing Iran’s nuclear weapons program. However, not limited by the agreement is Iran’s ballistic missile program, which continues to progress and threaten U.S. forces, partners, and allies in the Middle East and Europe.

The recent withdrawal by the United States has put the JCPOA at risk, but Iran assured its European counterparts that it will continue to adhere to the agreement if Europe is able to promise an open market for Iranian oil and no sanctions of any kind. Iran has also stated the parties cannot get involved in regional affairs and their missile programs, allowing for their program to develop while still assumedly stopping their civil nuclear enterprise.

Recent News

Iran’s ‘Khaybar Shekan’: The missile used by Tehran to attack in Syria

- Jerusalem Post: Iran showcased its Kheibar Shekan ballistic missile on Wednesday in an event in Tehran near the Azadi Sports Complex, Iranian pro-government media reported.

Click here to read more

Iran launches 3 satellites into space that are part of a Western-criticized program as tensions rise

- AP News: Iran said Sunday it successfully launched three satellites into space with a rocket that had multiple failures in the past, the latest for a program that the West says improves Tehran’s ballistic missiles.

Click here to read more

Three US troops killed in drone attack in Jordan, more than 30 injured

- CNN: Three US Army soldiers were killed and more than 30 service members were injured in a drone attack overnight on a small US outpost in Jordan, US officials told CNN, marking the first time US troops have been killed by enemy fire in the Middle East since the beginning of the Gaza war.

Click here to read more

Dena Destroyer to be Equipped with Vertical Launch Missiles

- Mehr News: Given the long-haul missions of destroyers, the impossibility of shore support in many cases and the variety of aerial threats, including fighter jets, drones and missiles, it is absolutely necessary to equip military vessels with air defense systems enjoying pinpoint accuracy, Tehran-based Tasnim News Agency reported Wednesday.

Click here to read more

Iran Guards Launch Naval Drills Near Strategic Gulf Islands

- The Defense Post: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards launched naval drills on Wednesday near strategic Gulf islands controlled by Iran but claimed by the United Arab Emirates, state media said.

Click here to read more

Iran Unveils New Vessels With 600-km Range Missiles, Conducts Surprise Military Drill

- Haaretza: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards’ navy has unveiled new vessels equipped with 600-km range missiles at a time of rising tensions with the U.S. in the Gulf, the semi-official Tasnim news agency reported on Wednesday.

Click here to read more

US deploys guided-missile destroyer to Middle East after Iran threats

- Al Arabiya: The US military has deployed a guided-missile destroyer to the Middle East after attempts by Iran to seize oil tankers increased in recent weeks. The US Navy’s Bahrain-based Fifth Fleet said on Sunday that the guided-missile destroyer USS Thomas Hudner (DDG-116) had entered the Middle East operating area on July 14 after transiting the Suez Canal.

Click here to read more

US mulls air defenses for Iraqi Kurdistan as Iran warns of renewed strikes

- Amwaj: A US congressional committee has called for a plan to deploy air defenses in Iraqi Kurdistan. If signed into law, the passed amendment to the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) will cover equipment and training.

Click here to read more

US sending F-16 fighter jets to protect ships from Iranian seizures in Gulf region

- WASHINGTON (AP): The U.S. is beefing up its use of fighter jets around the strategic Strait of Hormuz to protect ships from Iranian seizures, a senior defense official said Friday, adding that the U.S. is increasingly concerned about the growing ties between Iran, Russia and Syria across the Middle East.

Click here to read more

Iran moves toward possible atom bomb test in defiance of Western sanctions: intel report

- Fox News: A fresh batch of damning European intelligence reports reveal that the Islamic Republic of Iran sought to bypass U.S. and EU sanctions to secure technology for its nuclear weapons program with a view toward testing an atomic bomb. According to the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), which first published translations of the intelligence documents on its website, the security agencies of Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany revealed sensitive data during the first six months of 2023 on the Iranian regime’s illicit nuclear weapons proliferation activities. The reports mainly cover Iran’s alleged illegal conduct in 2022.

Click here to read more

US has military options for Iran’s nuclear threat, CENTCOM air force chief tells ‘Post’

- The Jerusalem Post: The US regularly updates its military options for threats from Iran’s evolving nuclear facilities, US Lt. Gen. and CENTCOM Air Force Chief Alexus Grynkewich told The Jerusalem Post in an exclusive interview.

Click here to read more

Iran’s ballistic missile capabilities are a growing threat to Europe

- Politico: As Europe struggles to combat Iran’s drone proliferation to Russia for use against Ukraine, it can ill afford to ignore improvements to an even greater unmanned aerial threat that may soon land on its doorstep: the country’s ballistic missile arsenal— the largest in the Middle East.

Click here to read more

First hypersonic missile range may be extended to 2,000 km: IRGC

- Tehran Times: Amir-Ali Hajizadeh, commander of the IRGC Aerospace Division, stated during a ceremony at the University of Mazandaran on Wednesday that the next version of the missile may have a range of 2000 kilometers as opposed to its present range of 1,400 kilometers.

Click here to read more

Iran likely supplies new batch of suicide drones to Russia

- The New Voice of Ukraine: Russia is conducting drone reconnaissance operations in the south of Ukraine, probably searching for new targets of a mass drone or missile strike, Ukraine’s South Operational Command spokesperson Natalia Humeniuk said on national television on June 25.

Click here to read more

Chinese Parts Help Iran Supply Drones to Russia Quickly, Investigators Say

- After Ukraine downed an Iranian drone, a Chinese part in the weapon showed it had been built and sent to Russian forces in three months

Click here to read more

Iran unveils first domestically-made hypersonic ballistic missile, claims it can evade US defenses: report

- Iran on Tuesday unveiled what officials are describing as its first domestically-made hypersonic ballistic missile, one it claims can “bypass the most advanced anti-ballistic missile systems of the United States” and “Israel’s Iron Dome.”

Click here to read more

Iran tests home-made Fajr-5 missile that has a thermobaric warhead

- Iran’s very own locally manufactured Fajr-5 missile, which has a thermobaric warhead, was successfully tested by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) Ground Force on Sunday, according to the Iranian Tasnim news agency. The Fajr-5 missile, a 333 mm rocket with a guided version known as the “Fajr-5C,” has already been handed to the IRGC Ground Force units, according to the agency. It was designed by experts at the Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization of the IRGC Ground Force.

Click here to read more

Tehran ‘already violating’ missile embargo set to expire in October

- Iran is violating a U.N. Security Council-mandated embargo on the export and import of missiles that is due to expire in October, Israeli observers of the Islamic Republic tell JNS. U.N. Security Council Resolution 2231, passed in 2015 to endorse the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action—better known as the Iranian nuclear deal—placed restrictions banning Iran from buying and selling ballistic-missile-related components.

Click here to read more

Iran transported advanced ASBMs to Hezbollah: Israeli media

- The Israeli occupation forces are preparing for a naval confrontation with Hezbollah amid reports of Iran successfully transferring advanced missiles to the Lebanese Resistance group and making progress in the Red Sea, Israeli media reported Sunday.

Click here to read more

Iran unveils new drones, missile systems

- Four divisions of the Iranian Army, namely the Ground Force, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Air Defense, held military parades marking the National Army Day on Tuesday in the presence of President Ebrahim Raeisi in Tehran.

Click here to read more

Iran test fires Sadid-365 anti-tank guided missile successfully

- General Ali Kouhestani, the head of the Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization of the IRGC Ground Force announced on Saturday during an interview with Tasnim news agency that there is a development of a powerful anti-tank guided missile called the Sadid-365. With a range of 8 km, the missile is capable of obliterating any armored equipment that it targets, according to Mehr news.

Click here to read more

Russia and Iran secret nuclear deal would allow uranium transfers to Tehran’s illicit weapons program: sources

- Amid the International Atomic Energy Agency’s disclosure this week that the Islamic Republic of Iran accumulated near weapons-grade enriched uranium for its alleged nuclear weapon program, Fox News Digital has learned that Iran has allegedly secured secret deals with Russia to guarantee deliveries of uranium. In what could be a major setback to a new Iran nuclear deal, foreign intelligence sources speaking on the condition of anonymity, and who are familiar with the negotiations between Moscow and Tehran over Iran’s reported illegal nuclear weapons work, told Fox News Digital that Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to return enriched uranium that it received from Iran if a prospective atomic deal collapses. The State Department would neither confirm nor deny the reports.

Click here to read more

Iran can make fissile material for a bomb ‘in about 12 days’ – U.S. official

- Iran could make enough fissile for one nuclear bomb in “about 12 days,” a top U.S. Defense Department official said on Tuesday, down from the estimated one year it would have taken while the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was in effect. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl made the comment to a House of Representatives hearing when pressed by a Republican lawmaker why the Biden administration had sought to revive the deal, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)

Click here to read more

CIA director says Russia is offering to help Iran’s advanced missile program in exchange for military aid

- Russia is likely offering Iran help with its advanced missile program in exchange for military aid for its war in Ukraine, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency said on Sunday. William Burns was speaking on CBS’ “Face the Nation,” where he noted that Iran had given weapons to Russia that were subsequently used in Ukraine, including in incidents where civilian infrastructure was targeted.

Click here to read more

Iran smuggled drones into Russia using boats and state airline, sources reveal

- Iran has used boats and a state-owned airline to smuggle new types of advanced long-range armed drones to Russia for use in its war on Ukraine, sources inside the Middle Eastern country have revealed. CIA director says Russia is offering to help Iran’s advanced missile program in exchange for military aid At least 18 of the drones were delivered to Vladimir Putin’s navy after Russian officers and technicians made a special visit to Tehran in November, where they were shown a full range of Iran’s technologies.

Click here to read more

How the West Can Help Thwart Russia’s Drone Assault

- Western backers could help Ukraine thwart possible “swarm” attacks by Iranian-made drones operated by Russia by focusing on certain key strategies, Newsweek has been told. Iranian-made Shahed-131 and -136 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can carry warheads that shatter or explode when they reach their target and have become a familiar sight across Ukraine, known for the low buzzing sound they make.

Click here to read more

- Iran has pursued the establishment of a comprehensive aerial defense network in Syria by sending equipment and personnel to the war-ravaged Arab nation in a project Israel has sought to thwart through repeated airstrikes, an intelligence source from a nation allied with the United States told Newsweek.

Click here to read more

- The White House released recently declassified documents that suggest Iran intends to deliver and train the Russian military with hundreds of “weapon capable” drones. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said, “Information indicates that the Iranian government is preparing to provide Russia with up to several hundred (unmanned aerial vehicles), including weapons-capable UAVs on an expedited timeline…Our information further indicates that Iran is preparing to train Russian forces to use these UAVs, with initial training session slated in as soon as early July. It’s unclear whether Iran has delivered any of these UAVs to Russia already”

Click here to read more

- In July 2022, Iran revealed its first ever “drone-carrier division.” The drones in this division are capable of being launched by both ships and submarines.

Click here to read more

- Iranian breakthrough of Israeli air defense: IRGC understood "how, when and what to shoot"

- Saudi Arabia activates US THAAD to deter looming Iran missile threat

- Senior Military Leaders Praise Destroyer Sailors during Souda Bay Visit

- Largest Patriot Missile Salvo In U.S. Military History Launched Defending Al Udeid Air Base Against Iranian Attack

References

[i] https://twitter.com/bbcpersian/status/1666156253184245760